ISSUE 02

- hippiechicky333

- Oct 8, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Oct 8, 2025

It started on the patio of the Royal American. He said I looked familiar, and honestly, I had no idea who he was. A voice in my head wanted me to say something cool like, “Yeah, I just have one of those faces,” but instead I rambled off every job I’ve had in Charleston, trying to find a common ground. Turns out he recognized me from Daps, the breakfast spot where I work.

We started talking about music, the way strangers do when they realize they share a bond, something simple, but as undeniable and beautiful as music itself. He mentioned he’d been part of the Charleston scene for a while. I asked, “You still play?” He smiled, “Yeah, I’m on in twenty.”

“Wait, sorry, who are you?”

“Wolfgang Zimmerman.”

Zimmerman has been part of Charleston’s music scene for more than a decade. He first made his mark as the drummer and producer for Brave Baby, but his influence extends far beyond the stage. Out of The Space, the studio he runs, he’s produced records for local staples like SUSTO and national acts like Band of Horses (Things Are Great, 2022). In recent years, he’s stepped out with solo work of his own, first with Spaceprints (2023) under both his name and Invisible Low End Power, and more recently with Demolition (2025) under his own name.

At that point, Enemy Magazine was less than a day old. I’d done some “research” before showing up at the venue that night, but clearly not enough to know what the guy actually looked like. So there I was, talking to the man I already had questions written for, making probably the least convincing debut as a music journalist. Luckily, he wasn’t just a musician in that moment. He was kind, generous, and quick to laugh at the irony of it all.

That night will always stick with me. I didn’t just land my first interview; I gained a friend, a teacher, and a spirit guide — all in one.

And since then, I’ve even come to learn his name.

For Wolfgang, drums weren’t a hobby; they were the thing. In kindergarten, the older kids were beatboxing and drumming on cafeteria tables, and he jumped in to join them. By the time he was eight, he had a little electronic drum kit and played it until it died. At ten, he and his mom mowed lawns all summer to buy his first real drum set.

“I was obsessed. Played every day, sometimes for hours, to the dismay of my neighbors in the small apartment complex we lived in.”

He started recording at twelve on a four-track tape machine, secretly stacking vocals and guitars over his drum parts. “I was kind of a lone wolf starting out,” he told me. But that didn’t last long.

Drumline pushed his discipline. Church gave him a stage.

Mentors like Bill Register, Brad Clarkson, and Hugh Allison made sure he kept growing.

Even then, he understood what it meant to live inside a song. “When you write a song in a certain emotional headspace, coming back to it months later can feel completely different because you’ve changed. That’s why early recordings can be so good, they capture who you were at that moment.”

By the time high school ended, there wasn’t a backup plan. “Anyone who knew me as a kid knows I had no other plan. It was only going to be music. Didn’t take the SAT, didn’t go to college. By the time I got out of high school, I already had a lot of clients and bands to record.”

Leaving Charlotte wasn’t running away; it was chasing something. The beach, friends, family, and the pull of a scene that felt wide open. “Deciding to move to Charleston was a revelation,” he said. “I came down here to start Brave Baby with Keon Masters and my cousin Christian Chidester and planned to just keep recording music.”

Those first years were raw and collaborative. He, Keon, and Christian shared their first practice space, a converted storage unit on Line Street. “At the peak of that place, it was like, ooo we need a sax player, and you’d just walk out to the parking lot and knock on a jam band’s door,” he remembered. “It was such a cool era. Just very DIY and collaborative.”

The underdog years lasted a while, but the turning point came with a show on the water. “For like 3–4 years, we always felt like underdogs… until we were the first band to headline the 1770 Records Harbor Cruise. It was the first time we sold something out and had no clue who like half the people were that were there.”

When Wolfgang talks about Brave Baby, there’s no sense of it being “back then.” The band’s still here, still working, and the way he remembers those early days only adds to the momentum they have now.

“We just had a lot of love and ambition together,” he said. “There was something about a Brave Baby song; it had to have an epicness to it.”

At first, he thought of himself as the drummer and producer, but that shifted over time.

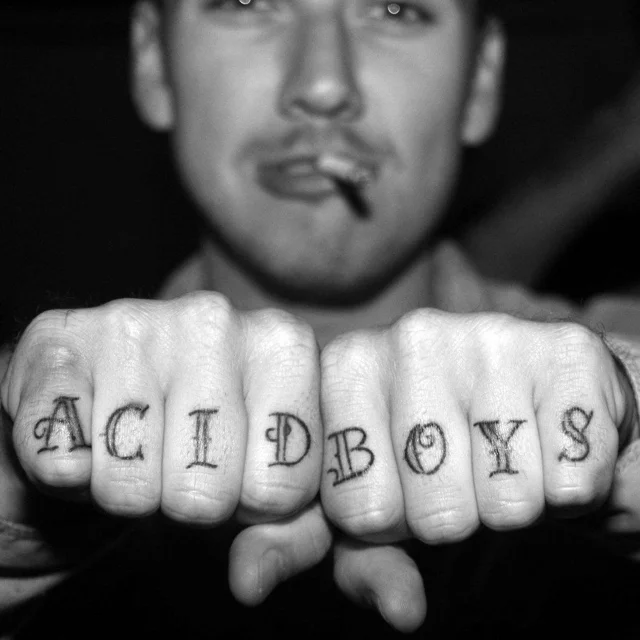

Photo: Dylan Dawkins

“Keon and I started to really link up on the songwriting front. We saw ourselves like a Lennon-McCartney type relationship, brotherly love but also sharpening each other to write our best. And Christian was our hands and coolness. He could always put the best bass, lead, or key riffs on songs to take our little acoustic jams and make them feel like they were ready for the Music Farm or something.

That 'scrappiness' carried them far enough to land a song like “Soothsayer” (2017), which later crossed five million streams. By then, the band had taken a break, but that kind of response pulled them back into the studio, leading to new music in 2021 and their 2024 album 3x Blood.

The Space feels more like stepping into Wolfgang’s head than into a studio. The walls are covered in memorabilia from everyone who’s recorded there, scraps of paper, old flyers, art, guitars, even stains in the carpet, and for each of them, Wolfgang has a story. He’ll tell it with a smile, and suddenly you realize it’s not just décor. It’s a web of memories and connections he’s built over years of friendship and work.

Knowing him now, it makes sense. This is the place where he funnels everything: creativity, frustration, joy, anger, and he’s opened it to others. He opened it to us, too. The Space isn’t just where music gets tracked; it’s where Wolfgang makes sure people feel like they belong. I asked him if he ever feels like more than a producer, maybe even a kind of translator for other people’s emotions.

He didn’t complicate it:

“The biggest thing is to just show up, no matter what. Good days, bad days, you have to show up and create.”

@wolfgangzimm

Wolfgang’s relationship with SUSTO goes back to when he was nineteen, convincing Justin Osborne to record in his Rock Hill basement. That basement session set off a connection that hasn’t let up. “Justin has been one of my best friends and favorite people in the world for a long time now,” he told me. “We had children around the same time, and we’ve shared a lot of life experiences together like that.” The way Wolfgang talks about Justin says everything: it’s all about honesty. “His first line of a song is the thing that ropes you in,” he said, quoting them like they were etched in his memory:

Those lines are a reminder of what he values: truth you can’t ignore.

With Johnny Delaware, the lesson was different. “He’s got this relic of the '70s

genius,” Wolfgang said. Johnny might flip a bridge into a chorus or find the part of a song no one else noticed. Where Justin leans into raw honesty, Johnny pulls

Wolfgang toward structure, instinct, and reinvention.

Johnny Delaware, who’s been alongside Wolfgang since his early Charleston days, talks about their friendship and the way it shapes how they work together. “I always feel so inspired around Wolfgang. Even before we hit record or sit down to track, ideas start coming through this open portal around him. There’s an energy in the room, and it always makes its way into the recordings.” That trust has only deepened over time. “I’ve never recorded a song with him and not felt proud of what we did together.” For Delaware, the bond is just as strong outside the studio. “He’s my spiritual brother for reasons beyond music. Those beliefs carry into the songs. We’ve both lived on the fringe, never really belonging or conforming, and I love that.”

Band of Horses brought another shift. Working on the album “Things Are Great” meant stepping out of basements and storage units into state-of-the-art studios, surrounded by names like Rick Rubin and Dave Fridmann. “Meeting larger-than-life producers… seeing how the gravy is made on bigger albums”, Wolfgang said. For once, he wasn’t doing everything himself; he had to sit with the songs, speak up, and trust that his instincts belonged in the room.

At Royal, he told me something that’s stuck since: “Sometimes a song doesn’t make the cut but leaves a kind of echo or ghost in new songs. It’s like an old version that has to die for the new one to be born.” That’s not a metaphor for him, that's how he hears it.

Songs don’t disappear; they haunt the next thing you make.

SPACEPRINTS (2023) was released under both Wolfgang Zimmerman and Invisible Low End Power. When I asked him why, he admitted it came down to indecision: “Honestly, I couldn’t decide what to go with. I already had a Wolfgang page made, and I was playing shows with the live band as ILEP. I had some help on that album with folks that played in the live band for ILEP over the years, so I kinda saw it as my solo album and also a band album.”

That mix of identities comes through in the music. The record moves on rhythm, with drum and bass as its core, but it’s the synths and keys that give the songs their shape. It leans on 80s new wave and synthpop textures, reshaped with the psychedelic pull of Tame Impala, the eccentric pop of MGMT, and flashes of Kravitz-style funk. Specifically, on track 5, “The Force,” percussion drives while synths bend around it; whereas number 7, “Talk a Walk”, brings in a funkier groove, colorful and hypnotic. The concept of Invisible Low End Power started with a striking image too: “For the longest time, the idea of ILEP was two drummers up front, me singing and playing, with the keyboard, bass, and guitars behind the drums.” Even if that setup shifted over time, that spirit of collaboration and experimentation still runs through the record.

Demolition (2025) opens with its title track, drums hitting hard, less like that familiar groove and more like an outlet for everything he was carrying. That outlet has always been there: “I definitely had some anger issues as a child that I transmuted by beating the heck out of the drums.” The record itself was born out of heartbreak and betrayal, and Wolfgang didn’t hide it: “Those songs I made to get by. They’re pretty raw, and I basically just finished up as best as I could stomach and put the record online.” You can hear that rawness in “Chase You Down,” where his voice is almost unguarded, and in “Alabaster” and “State of the Artist,” which carry a calmer tone. Both are built with beautiful compositions that give the record moments of reflection without erasing the hurt underneath.

I love that these two records don’t mirror each other, but it's as if they collide. One points outward, the other turns inward. Where SPACEPRINTS is a conversation with others, Demolition is a fight with himself. Both albums reveal him, just from opposite ends of the spectrum.

These days, Wolfgang splits his time between raising his two daughters, producing other people’s records, and still finding the space to make his own. Fatherhood forced him to be sharper with his time:

“It’s definitely made me a little bit more by the book in terms of the business side of things… it also really makes me waste less time. When I was younger, I had so much time and didn’t always put it to the best use. Now if I’ve got an hour to myself, I really lock in and create.”

That discipline feeds into something bigger. Music isn’t just work for Wolfgang; it’s tied to his faith, something he lost and found again. In our first conversation, he told me, “I used to try channeling energy and offering myself up, but now I just want to be myself and let the music come through.” Later, he explained how that perspective changed the way he listens:

“If we’re at our best, we’re using ourselves as the vehicle by which art and magic move through… songs naturally have a mystical spiritual sense to them too. You’ll be working on someone’s music, and that song will be directly talking to you about what’s happening in your life that day.”

What I take from Wolf’s words is that producing isn’t about control, it’s about being open enough for the music to show you where it wants to go. That resonates with me, because it’s the same way I’ve come to see writing and playing; if you try to force it, you lose the thread. If you let it move through you, it tells you something real.

When I asked if he ever thought about legacy, he kept it simple: “I want to make records until I’m an old, old man. I hope when I leave the earth that a few people can look at the offerings I’ve left behind and sense some truth and originality behind it and find something to love and pass on.”

In the meantime, he’s focused on the people around him, the artists he produces, the younger bands he encourages, the friends whose songs he still finds himself inside of.

Nick Matthews had just finished a new project with Wolfgang when he told me the experience felt almost otherworldly. “Working with Wolf was a godsend,” he says. In the studio, Matthews watched Wolfgang layer in details that most people would never even notice, subtle sounds that quietly reshape a song.

“The little things...the bells and whistles...might go unnoticed, but they completely elevate the track.”

The way Wolfgang works even reminded Matthews of another heavyweight he’s collaborated with. “He’s so much like John Gilbert, who produced Flipturn and Mt. Joy. Sometimes I actually have to stop and remind myself they’re two different people.”

But what sticks with him most isn’t just the craft, it’s the connection. “Wolf’s a fun collaborator. Once you click with him, that’s it. Game over. You’re going to make some really cool stuff.”

He had just finished telling me that he tries to be the kind of person he once needed, a mentor, a big brother in the scene. That wasn’t just talk. From the start, Wolfgang has opened his studio to us, introduced us to people we might never have met, and treated Enemy like it belonged here before it even had its footing.

“I try to treat everyone how I wanted to be treated when I was starting out. Now I’m kind of like a big brother or mentor, which I really like. I want to help bring people up.”

That outlook goes beyond music. He’s setting a standard for how people should be treated: with respect, patience, and a belief in what they’re doing.

No matter where they are in their process.

Enemy isn’t his story alone, but it wouldn’t be the same without him. He’s more than the subject of this issue; he’s become part of its backbone. In a real way, part of Enemy belongs to Wolfgang Zimmerman.

Because writing about Wolfgang isn’t just about retracing the path of one musician. It’s about recognizing how his journey, from Charlotte drumlines to Brave Baby, from long nights at The Space to producing records that echo far beyond Charleston. Everything from then until now and in between... it has all shaped the sound and spirit of this scene. It’s about the people he’s lifted up, the trust he’s earned, and the way he’s carried music through every role: drummer, producer, songwriter, mentor, father, friend.

Ryan "Wolfgang" Zimmerman isn’t just part of the story we’re telling; he’s part of the reason we’re here to tell it.

Comments